Reading, particularly fiction, is a dynamic and multisensory activity and experience involving cognitive, affective and embodied processes. It can offer comfort, resonate with personal experiences, or transport readers to imagined worlds. Thus, there are no straightforward answers to what makes literature healthy. It is, as one can imagine, a broad topic, and many through history have hypothesized about the qualities such texts that provide “health effects” may have. This paper examines the question from an empirical angle by presenting and discussing research within the interdisciplinary field of the Empirical Study of Literature (Kuiken and Jacobs 2021), where researchers work on applying empirical methods to study the structure, function and effects of literature, which require data from actual readers.

Table of Contents

Defining Literature and Health

Given the range of definitions of “literature” and “health,” it is necessary to clarify these terms. First, health is understood here through the World Health Organization’s definition of well-being as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO 2020), with literature’s potential health effects primarily relating to mental and social well-being.

Second, I follow The Handbook of Empirical Literary Studies (2021), which defines literature as “texts that embody literary devices”, which distinguishes it from ordinary language. Louise Rosenblatt (2005 [1956]) further describes literature as providing “a living through, not simply knowledge about” , granting readers access to lived experiences.

How to Make Literature Healthy?

The Premise and Its Challenges

The question “What makes literature healthy?” may itself be problematic, as it presupposes that literature can be healthy—a premise explored by the literary scholar Josie Billington in Is Literature Healthy? (2016). She argues that literature risks becoming instrumentalized when it is brought into health contexts, as often occurs in bibliotherapy, where texts are selected to address specific issues, and the intervention is tied up to a specific agenda or a programmatic therapy. Instead she illustrates, through personal and shared readings of literary works, how reading and engaging with literary texts might function therapeutically when freed from targeted outcomes and agendas.

Literature as Language for Human Sorrows

According to Billington, the principal value of literature lies in its provision of a language through which human sorrows, or life’s fluctuations in general, may be expressed. Finding language for our human sorrows seems essential for our well-being so these do not become incommunicable and turn into traumas. Another potential health benefit is that reading can mitigate feelings of isolation by fostering a sense of connection through shared human experiences. In this way, literature offers insight into what it means to be human.

Literary Thinking Beyond Prescription

Aligned with Billington’s perspectives, I suggest a departure from the simplistic view that literature functions as a form of “medicine” or a “cure.” Rather than offering prescriptive knowledge, definitive solutions, or instructional guides for living, it might be more fruitful to look at literature as a source of inspiration and creativity that helps to find solutions, meaning or comfort in life or to restructure our thinking and feelings.

Billington (2016) terms this profound engagement with literature “literary thinking”, where literary texts can give access to a thinking mode that goes beyond our daily language: “that literature can ‘think’ reality when ordinary human thought falls short; that a book can have thoughts that humans cannot have”.

The Role of the Reader

Literary thinking can also be explained as a blend between the book and the reader’s thoughts. Billington argues that literature can create more “healthy minds”, but that it also requires a reader who is able or willing to engage with reading at a deep level, meaning in a profoundly emotional and personal way. She concludes that literature’s therapeutic potential arises when it is not trying to be so, and that literature, in that form, has a potential role and power similar to psychoanalysis, a role that seems lost in our modern society.

Historical Perspectives on Literature and Health

Throughout history, many within various fields have theorized ideas of literature as healthy or transformative. For example, in Poetics (1961 [around 330 BC]), Aristotle argued that an audience’s accumulated feelings during a drama play would be released in the end through what he called Catharsis (rinse of feelings). Aristotle believed that drama and poetry would support people’s personal development and healing by bringing out these feelings.

Central to the various connections between literature and personal growth or change is the idea of art and literature as an experience that gives access to lived experiences (Dewey 2005; Rosenblatt 1938). In addition, engaging with others’ lived experiences is an active rather than passive activity that involves the reader’s self and can be potentially transformative (Gadamer et al. 2013). These early theories of the function of literature have been essential for how aspects of literary reading have been operationalized and studied later empirically.

The Interplay Between Text, Reader, and Reading Engagement

Summing up, when exploring the health potential of literature, it is insufficient to look at the text in isolation. Instead, the question should be addressed by investigating the interplay between text, reader, and a mode of reading engagement that facilitates a “literary thinking.”

Empirical Studies of Literature

In the book Reading and Mental Health (2020), Corcoran and Oatley identify two main aspects where literature potentially can contribute to mental health:

- Understanding others

- Self-understanding

However, these are highly interrelated; we can come to understand ourselves better through others and vice versa. Therefore, I will address them by focusing on three central areas explored in empirical studies of literature:

- Foregrounding

- Empathy and Immersion

- Self-Altering Literary Reading

Foregrounding

Definition and Concept

Billington’s concept of “literary thinking” refers to the reading of “serious” literature, where language and style play a crucial role. To understand the text’s significance, the concept of foregrounding (van Peer et al. 2021) is useful, as it helps explain how literature can shift readers from automatic processing to literary thinking.

Foregrounding can be defined as stylistic features in texts perceived as striking or deviating, causing defamiliarization (van Peer and Hakemulder 2006). These deviations could be at a grammatical, syntactic, or semantic level. However, foregrounding does not exist without a reader, as the reader varies what is perceived as foregrounded (Hakemulder 2004).

Historical Roots

The core idea of foregrounding can be traced back to Aristotle’s Poetics, where he argued that a text should distinguish itself from everyday language by using unfamiliar terms, strange words, and metaphors. Russian structuralist Victor Shklovsky later described this as “making strange,” explaining that “Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony” (Shklovsky 2006 [1917]).

Example: Shared Reading Session

To illustrate a foregrounded experience, the paper introduces a Norwegian online Shared Reading (Davis 2009; The Reader n.d.) session for cancer patients featuring Olav H. Hauge’s poem “Konkylie.”

Konkylie

Du byggjer di sjel hus.

Og du skrid stolt

i stjerneljoset

med huset på ryggen,

likesom sniglen.

Ottast du fåre,

kryp du inn i huset

og er trygg

bak hardt

skal

Og når du ikkje er meir

skal huset

stå att

og vitna

um di sjels venleik

Og di einsemds hav

skal susa

der.

(Olav H. Hauge 1951)

Overall, we experienced the poem as very strange. It presents an image of “building a soul’s house” and compares it to a snail that “strides proudly with the conch on the back.” In the second part, the simile becomes a metaphor for legacy, as the snail disappears, and the house is left there. Below is an extract from the dialogue between the facilitator (Reader Leader), the participants, and me centered on the deviating word combination “soul’s house.” The extract is translated by the author into English:

Rachel: I think it is a very beautiful poem with very beautiful language. Big words. But … I find it difficult to sort of concretize it.(…)

Reader Leader: Yes because it is big things. Like it is not like you build your soul’s house, like. The soul is like … it is everything we have in a way, or what is soul?

Tine: Maybe identity.

Reader Leader: Yes. Yes, but that is like these words we use, like soul. But do we think about what a soul is? I don’t know if any of you do that. Soul. Soul.

Rachel: I think like it is that you said that it is … the soul is actually everything we are and everything we do. Like that is … Everything that will be gone when you die then.

Neurocognitive Studies and Foregrounding

Neurocognitive studies have used brain images to see how the brain responds to reading, for example, by using more unusual words (Bohrn et al. 2013; Keidel et al. 2013). Other studies have used more qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews or think-aloud protocols, to understand actual readers’ experience of foregrounding and the language used to describe these experiences.

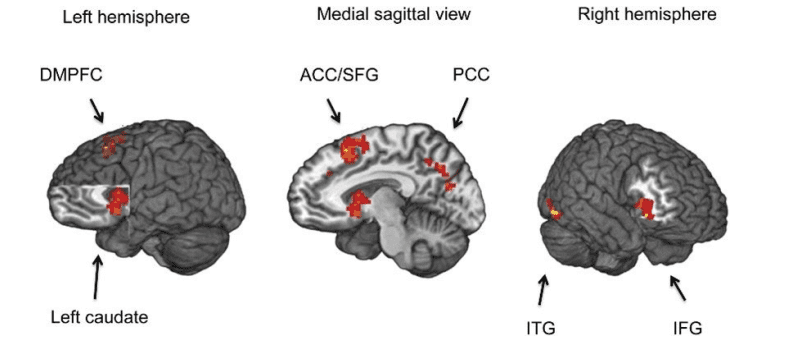

Foregrounding is related to the reader’s experience of something striking in a text. Thus, foregrounding and health may seem quite apart from each other. So, to understand how experiences of foregrounding may enhance well-being and create “healthy minds”, I will present a neurocognitive study that sheds light on what happens in the brain when we read deviating language. Below is an image of the activation of different brain areas while reading Shakespeare. In this study, Keidel et al. (2013) gave participants sentences to read and measured their brain activity while reading.

Functional Shifts and Brain Activation

Half the sentences had a functional shift, which is a word whose usual grammatical function has shifted. Functional shifts can surprise the reader because they deviate from the daily language. As an example, in the following two sentences the functional shifts are in bold: “She was so beautiful that she gladly windowed her body to every eye around.” (Antony and Cleopatra, IV.xiv.72) and “It was not just a handshake she offered you; she also lipped you a kiss as she left.”.

In the first sentence, “window” is a word normally used as a noun but has shifted function to a verb. The same goes for the word “lipped” in the second sentence. For the other half of the sentences, the researchers had replaced the functional shift with a word that conveyed the same meaning but is more used in daily language; instead of “windowed,” they used “displayed” and “lipped you a kiss” was replaced with “blew you a kiss.”

Interpretation of Findings

The researchers found that the functional shifts activated brain areas beyond regions classically activated by typical language tasks. This included both the left and right sides of the brain and networks that are usually involved in processing non-literal aspects of language. The researchers hypothesize that this is due to an extra effort required by the reader to make sense of the sentence; the functional shift forces the mind away from automatic language processing and makes it search for new pathways for meaning.

These findings seem central to understanding how literature’s deviating language can activate and stimulate the imagination. However, the findings need to be read with some caution, since they are based on reading sentences in a scanner, which far from resembles an authentic reading situation. Still, the study provides insight into the complexity of poetic language and how deviating language may challenge our brains in a way that other types of texts may not do.

Foregrounding and Refamiliarization

Returning to foregrounding research, studies suggest that the encounter with foregrounding not only leads to a defamiliarizing effect but also involves a process of “refamiliarization” (Fialho 2007; Miall and Kuiken 1994) as a strategy to make sense of what at first seems strange. This process is guided, Miall and Kuiken (1994) argue, by the feelings the text evokes in the reader. To explain the process of refamiliarization I will go back to the Shared Reading session I introduced previously. Further into the dialogue, Molly, another participant suddenly speaks up after being silent for a long period of time and condenses the poem into one line: “Which house remains after me?” and thus connects the poem to her own life.

Example from Shared Reading

Rachel: What Molly said it was very like … I agree very much, it is what I maybe also extract from the poem. And it is something I am very occupied with and aware about since I have a cancer diagnosis with a quite bad prognosis. So, it has become very important for me then and become very … become one of the things I think about every day. What is important for me today, what is important that I give my family or that we are going to have together or …. Like it is nothing of that which … it resonated actually very well with me. Mmh.

Interpretation of the Example

In light of the idea of refamiliarization, one could say that Molly and Rachel are refamiliarizing the poem by translating the strange image of building a soul’s house into something familiar for them and connecting it to their life situation. At the same time, they may understand or be more aware of their own experiences by connecting an image to it. Thoughts around mortality and legacy were not unknown to the participants. Both Rachel and Molly expressed a profound resonance with the poem’s theme as they had thought extensively about their existence and meaning in life when they got ill.

Cognitive Implications of Refamiliarization

The process of refamiliarization can potentially lead to self-perceptual changes in the reader by providing insights and new ways of understanding and connecting things (Kuiken et al. 2004). Perhaps this refamiliarization process was what the researchers could observe on the brain images while reading sentences from Shakespeare; the words with functional shifts required using a larger part of the brain to refamiliarize it and perhaps even imagine the situation.

Due to this disruption in the reading process that foregrounding may cause, readers are believed to dwell longer on these passages (Miall and Kuiken. 1994). This observation has led to the hypothesis that foregrounding creates less flow and immersion in the reading process. However, others argue that foregrounding and immersion can co-exist, and foregrounded passages can even lead to a deeper level of absorption (Kuijpers et al. 2017).

Foregrounding and Reader Effects

Foregrounding research has investigated how a reader’s processing of foregrounding may elicit an understanding of self and others in terms of reported empathy (Koopman 2016; Scapin et al. 2023), reflection (Koopman and Hakemulder 2015), and self-perceptual change (Fialho 2012; Fialho 2007; Kuiken et al. 2004; Miall and Kuiken 1999). One important thing to emphasize is that these effects do not come from the existence of literary features experienced as foregrounded in a text per se, but from the depth of processing. Foregrounding requires effort, and readers may reject the text as too strange or difficult, resulting in shallow processing or failed foregrounding (Harash 2022; Scapin et al. 2023).

Limitations of Current Research

Despite valuable insights from foregrounding research, studies often rely on self-reported experiences and face challenges in capturing authentic reading. Experimental settings using isolated sentences or extracts may disrupt immersion, producing results that may differ from natural reading contexts, such as reading comfortably at home. Thus, the field needs studies that can collect data from actual readers and authentic reading situations. Here, the reading-group practice Shared Reading seems promising because the immediate text responses are articulated in a collective setting and can be recorded and studied (see, e.g., Billington et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2016; Dowrick et al. 2012).

Empathy and Immersion

Research shows a small and positive effect of reading on empathy and “Theory of Mind” (Dodell-Feder and Tamir 2018; Mumper and Gerrig 2017). Theory of Mind is the ability to understand other people by ascribing mental states to them. It includes the understanding that others’ beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and intentions may be different from your own. Theory of Mind is thereby essential for everyday social interactions. Reading literature has been associated with Theory of Mind, as it can offer “simulations of the social world” (Oatley 1999), a safe place where readers can engage and immerse themselves into social interactions without consequences as in the real world.

Oatley characterizes this immersion into a story and its characters a “meeting of minds” (Oatley 1999). However, these simulations and meetings are not copies of the real world but are made and designed. Due to this idea of fiction as simulations of social experiences, where readers train interpersonal skills, people who read fiction have been hypothesized to be more empathic and better at mentalizing. Thus, reading can potentially enhance social well-being by understanding others better and being able to cooperate with others.

Measuring Empathy and Theory of Mind

Theory of Mind has mainly been measured with the use of “Reading the Mind in the Eyes test” (Baron‐Cohen et al. 1997), which is a series of faces with only the eye part visible, where participants need to label the emotion or mood of the person. In an experimental study, Kidd and Castano (2013) compared readers who read an essay with those who read a fictional story and found that the latter scored better on the test. However, the results have been difficult to replicate, and it remains unclear whether reading fiction increases empathy or if more empathic individuals are drawn to fiction.

Moreover, it is debatable whether labeling the right emotion is enough to access the Theory of Mind. The validity of measuring empathy immediately after reading has also been questioned, as effects may more likely develop over time. Addressing this, Bal and Veltkamp (2013) measured empathy and emotional transportation before, right after, and one week after reading, and found that immersion during reading correlated with higher empathy, suggesting that deep engagement with a story may foster greater understanding of others.

Fiction, Non-Fiction, and Cognitive Openness

Narrative absorption would make fiction particularly useful for enhancing empathy. Nevertheless, would the same effects occur when reading non-fictional texts about other people’s lives? Studies by Djikic et al. (2009, 2013) gave readers a variety of texts and found that only when the text was perceived as fiction did they report self-change. The researchers suggest that fiction fosters greater openness and tolerance toward the content. An explanation for this cognitive openness while reading can be explained through the TEBOTS theory: “Temporarily expanding the boundaries of the self ” (Slater et al. 2014).

The theory is based on the idea that humans have a need for expanding self-boundaries, which is an underlying motivation for seeking narratives. Being engaged in narratives can give us a break from the constant task of maintaining our personal and social identity. When reading fiction, we can immerse ourselves in other worlds, persons and situations, and we can, with a more open mind than in the real world, take in alternative ways of thinking and being.

Self-Altering Literary Reading

Responses to literary texts combine verbal, emotional and cognitive elements. However, how readers engage in reading is central to the weighting of each and for possible outcomes. I will focus on one mode of engagement that has been addressed in phenomenological studies and is labeled “Expressive enactment”.

Expressive Enactment and Self-Implication

This reading mode facilitates a movement toward words that “fit” the feelings elicited by the text, thus going deeper into characterizing the defamiliarizing and refamiliarizing processes. Expressive enactment represents a self-altering reading where the boundaries between the events within and outside the text become blurred because the reader implicates the self in the reading in a deeply personal way. “Self-implication” (Kuiken et al. 2004) occurs when there is a felt connection between the reader and the text.

It is an “inexpressible realization” (Kuiken et al. 2004) which covers the experience that the text has touched something in the reader, but the reader is not able to pinpoint what it is yet. This may have been the case for Rachel during the Shared Reading session, where she described the poem as beautiful, but difficult to articulate.

Emotional Engagement and Emergent Thinking

Emotional engagement seems key in this process of understanding and finding words for the felt sense, which activates “emergent thinking”. In addition, “self-modifying feelings” may occur, which “restructure their [the reader’s] understanding of the text and, simultaneously, their sense of themselves”.

Example: Rachel’s Reading of “Konkylie”

If we go back to the dialogue in the Shared Reading session to Rachel’s experience of the poem “Konkylie,” the Reader Leader asks further into the conversation:

Reader Leader: So you are building your soul’s house?

Rachel: Yes, I feel actually I am doing that. Yes. Occupied by that, to think how … what kind of house shall stand by after me. It is a very important part of what I do and say during the day. I am aware that there must be …. Well, in any case, for my family, for the kids, then there must be good memories to look back on. There must be happiness and laughter and coziness [hygge] and safety, and not heavy and sad and angry or …. So, it is actually a, like, an important thing then.

Rachel engages deeply with the poem, realizing she is “building her soul’s house” and using its language to express personal reflections. Rachel’s reading experience is an example of how literary language, literary thinking, can become a resource when coping with existential questions, in this case the difficult feelings connected to the awareness and acceptance of her own legacy.

Discussion and Future Research

In this paper, I have approached the question “What makes literature healthy?” by exploring different characteristics that may support health. A look into foregrounding research has helped to understand how literature can facilitate a shift from automatic processing, which can create a more flexible mind as it involves cognitive processes that can be healthy for psychological well-being and self-development. Reading literature also involves immersive and emotional engagement that both moves us closer to others’ way of thinking and, at the same time, connects it to ourselves, and here there can both be social learning as well as self-understanding. In this immersive experience, self-implication and identification may be particularly important in terms of how literature can be transformative.

The Role of Emotional Engagement and Shared Reading

Overall, what makes literature healthy may lie in its capacity to provide language for understanding ourselves and others a little better. Through deep reading, literature can help us to find words to express and understand our own “human sorrows” or lived experiences in general. Emotional engagement seems key in all three aspects, and through expressive enactment the reader’s feelings, evoked by the text, modifies the reader’s understanding of the text as well as the reader’s self. Transformative reading experiences are lived examples of how literature can become a support in readers’ lives, and we thus need more research to capture and investigate characteristics and implications of these experiences.

Text–Reader Interplay and Community Practices

Then the question is not only a matter of the text, but an interplay between text, reader, and the mode of reading engagement. Potential transformative effects require a reader who is ready to engage, and here, community reading practices, such as Shared Reading, can be particularly fruitful in creating a space that invites and facilitates deep processing of literary texts. Shared Reading might more easily facilitate foregrounding processes of defamiliarization and refamiliarization, as it seemed to be the case with the Shared Reading of the poem “Konkylie.”

This is partly due to the presence of a skilled facilitator who can guide the participants deeper into the text, and partly due to a collective and personal meaning-making process, where the participants open “doors” in the text for each other (Kristensen et al. 2023). To facilitate this deeper mode of reading, “literary thinking” (Billington 2016) is particularly important to give access to an essential resource for coping with “human sorrows.”’ In addition, Shared Reading emphasizes and explores personal connections between text and reader involving memories, feelings and reflections.

Gaps and Directions for Future Research

However, important perspectives are still missing in understanding how literature works in practice and its relation to health. These can be gained from future reading studies that take place in authentic reading settings, and here, Shared Reading may be one option; diary-assisted reading (Green 2022) could be another. Understanding the full potential of literature as healthy also requires insight into its long-term impact, not only reported or measured effects immediately after reading. Finally, the majority of research within empirical literature studies focus on adult readers; studies on younger readers are missing— studies, for example, on youngsters who might particularly benefit from reading fiction when being in a personal developmental stage.

Conclusion

However, to better comprehend the possible answers to the question it is necessary to explore actual readers’ reading experiences and cases where literature becomes “healthy” or transformative. This paper, and my doctoral dissertation, provides in-depth insights into how literature can become a resource when going through and coping with serious illness.

The example from the Shared Reading, where a poem provided language/an image to express existential matters, illustrates how literature can help with what we as humans may find difficult to grasp and express. This paper also wishes to explicate that the function of art and literature in our society should not be perceived as “frosting” to life but as a necessity to support coping with life’s sorrows and to interact with human matters.

More Post

- How AI Is Reshaping Education Policy and Teacher Workflows

- EU Social Policy, Skills Investment, and the Green Transition

Hi, I’m Anshul Patel, author and co-founder of TigerJek.com. I am a long-time Roblox and mobile gaming enthusiast with 6+ years of gameplay experience. I test every method, build, and strategy personally before writing guides for TigerJek. My goal is to simplify complex games and help players progress faster.