As the world—and the European Union in particular—navigates turbulent times, specific strategies have been implemented to address ongoing challenges that threaten citizens’ lives and working conditions. Advancements in EU social domains have always been constrained by legal, political, and financial obstacles, even though it is accepted that EU institutions play a crucial role in shaping member states’ public policies in areas related to workers’ rights and employment conditions.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The increasing regulation of social policy issues at the supranational level goes along with a growing willingness to further reconcile economic, social, and ecological goals (Sabato et al., 2022, p. 199). Among the challenges pertaining to the trajectory and scope of EU social policy lies the need to reorient the economy toward a greener and environmentally sustainable path (Im et al., 2023; Pociovălișteanu et al., 2015).

Achieving this goal—aligned with the evolving industrial and technological landscape and strategies of member states—requires preparing workers for new employment opportunities, “green jobs” in more environmentally sustainable industries (Sikora, 2021). Authors like Fischer and Giuliani (2025) emphasise how important it is for EU institutions to address environmental and social goals and policies in an integrated manner, within a “new growth model” (Koch, 2025).

2. EU Policy Framework

2.1 The European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) and the European Green Deal (EGD)

As examples of this commitment, two key initiatives were recently supported by the European Commission in the areas of employment, social protection, and environmental policy. The first is the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR), proclaimed in Gothenburg in 2017, which addresses critical social dimensions such as equal opportunities, fair working conditions, and social protection (European Commission, 2021). The second is the European Green Deal (EGD), a flagship initiative of the first EC led by Ursula von der Leyen (2019–2024), which aims to achieve climate neutrality and promote a just ecological transition by 2050 (European Commission, 2019a).

2.2 Research Gap and Aim of the Study

A growing body of literature has traced the historical trajectory that led to the launch of these initiatives (Hacker, 2023), analysed their political and legal characteristics (Arabadjieva & Barrio, 2024; Zeitlin & Vanhercke, 2017), and highlighted the strategic role of key actors in shaping recent EU social policy (Dura, 2024). However, the impacts of these policy measures on the everyday lives of EU citizens—beyond aggregate quantitative indicators and their evolution at the country level—remain insufficiently explored. This article seeks to fill this gap by analysing a specific set of training programmes for low‐skilled unemployed individuals, implemented by a local unit of the Portuguese Employment Service (PES) in the central region of Portugal.

2.3 Research Question

Our research question is: To what extent do training programmes implemented in Portugal under the EU’s social policy agenda equip low‐skilled and under‐qualified unemployed individuals with the skills needed to adapt to ecological and digital transitions and secure stable employment?

3. Analytical Approach

3.1 Historical Institutionalism Framework

This article adopts a historical institutionalist approach to examine why active labour market policies (ALMPs) in Portugal—particularly those aimed at vulnerable unemployed individuals—have evolved incrementally despite supranational pressures for reform. Informed by the contributions of Pierson (2000), Mahoney and Thelen (2010), among others, it analyses how past policy legacies, critical junctures (such as the eurozone crisis), and institutional path dependencies continue to constrain the capacity of PES to implement more transformative social investment approaches.

While European Union initiatives like the EPSR promote ambitious activation and re‐skilling agendas, these goals often clash with entrenched bureaucratic routines, fiscal constraints, and segmented labour markets typical of Southern European welfare regimes. Rather than radical change, the Portuguese case illustrates a pattern of institutional layering and drift, in which new policy objectives are grafted onto existing structures without fundamentally altering their logic or effectiveness.

4. Empirical Focus and Methodology

4.1 Description of Programmes

The programmes analysed correspond to the following EU‐standardised categories: (a) apprenticeship courses (for example, automotive mechatronics technician) with dual certification (upper secondary school diploma (12th year) plus EQF Level 4 vocational qualification); (b) adult education and training (EFA) courses with a “school‐leaving certification pathway” (equivalent to upper secondary education); and (c) courses from the “Vida Ativa” (active life) programme, with, for example, a medium‐duration vocational training in secretarial studies.

4.2 Bureaucratic and Discretionary Dynamics

These programmes reflect both continuity and adaptation. On the one hand, they remain governed by bureaucratic requirements—such as minimum cohort sizes and mandatory full‐time attendance—and by compliance with EU agency guidelines and policy frameworks. On the other hand, caseworkers retain a degree of discretionary flexibility in interpreting and applying these rules, particularly when determining participant eligibility. These discretionary practices are shaped not only by local labour market conditions, administrative capacity, and budgetary constraints, but also by longstanding institutional routines. From a historical institutionalist perspective, this interplay between formal regulation and bounded discretion illustrates how new policy objectives are layered onto existing structures, often without fundamentally altering the underlying institutional logic.

4.3 Data Collection and Analysis

This article’s empirical analysis is anchored on 29 semi‐structured interviews conducted between November 2019 and March 2020. The study involved 23 working‐age individuals and six interviews with stakeholders. The first group consisted of individuals who were either temporarily unemployed or who had been labour market inactive for more than 12 consecutive months, some of whom had been out of work for a significant period. Their ages ranged between 21 and 63 years old, and they were enrolled in various training programmes.

The second group comprised stakeholders with distinct roles, expertise, and levels of responsibility. All interviews were transcribed and subjected to thematic analysis using both deductive and inductive coding (Knott et al., 2022). We conducted 23 interviews with programme participants, focusing on their expectations regarding the training experience and anticipated labour‐market outcomes. In addition, we interviewed two front‐line caseworkers and two trainees to explore the administrative and organizational dimensions of programme delivery. Finally, two senior managers at the Institute of Employment and Vocational Training (IEFP) were interviewed to examine the agency’s evolving role—particularly since the 2008–2009 crisis—its coordination with national and EU partners, internal performance challenges, and changes in the training portfolio.

5. Activation and Skills Investment: Cornerstones of EU Social Policy in Recent Years

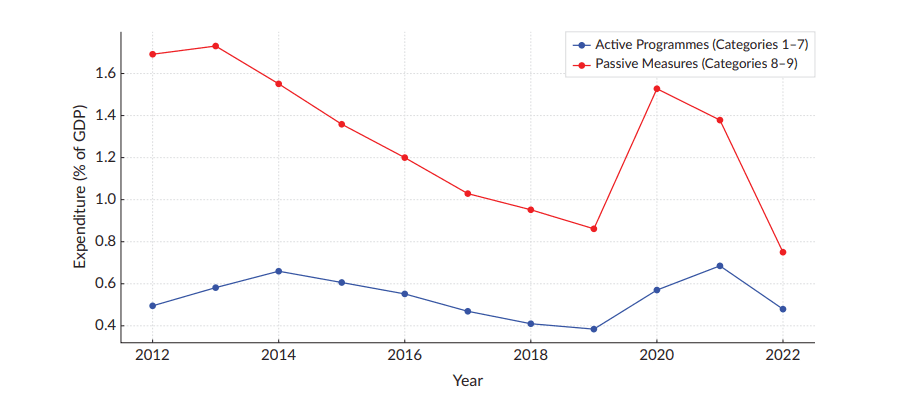

Among the distinctive features shared by most EU member states is their commitment to the so‐called European social model, a set of common principles and goals aimed at ensuring economic growth alongside social progress and cohesion (Hemerijck, 2018). Within this framework, “activation” and “skills investment” have emerged as two of the most prominent policy orientations over the past two decades. Both reflect a broader shift towards what is commonly described as a “social investment paradigm” (Morel, Palier, & Palme, 2012), which seeks to reconfigure welfare systems by prioritizing human capital development, lifelong learning, and labour market participation over passive forms of income support.

The European Employment Strategy (EES), launched in 1997, and the Lisbon Strategy (2000) set the foundations for the diffusion of activation policies across Europe. The Europe 2020 strategy further consolidated this orientation, with explicit targets for employment, education, and social inclusion. These strategies encouraged member states to promote employability and adaptability, reduce long‐term unemployment, and align training provision with labour market needs.

In this regard, EU institutions—particularly the European Commission—have played an increasingly active role in framing activation and skills policies through instruments such as the European Semester, the European Social Fund (ESF), and, more recently, the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). These mechanisms not only provide financial incentives but also shape national policy priorities through country‐specific recommendations and monitoring frameworks.

However, despite rhetorical emphasis on “upskilling” and “reskilling” as tools for inclusive growth and ecological transition, the practical implementation of these agendas remains highly uneven across member states. National institutions, labour market structures, and welfare regimes mediate the adoption and outcomes of EU‐driven policies, often leading to significant variations in the quality and inclusiveness of activation measures (Bonoli, 2013; van Vliet & Caminada, 2012).

Portugal provides a particularly interesting case in this regard. As a Southern European welfare state characterized by a relatively low level of social spending, segmented labour markets, and a high incidence of precarious employment, Portugal faces persistent structural challenges that limit the reach and effectiveness of activation and training policies (Cardoso, 2021). Although successive governments have embraced EU social investment rhetoric, the actual implementation of activation strategies often reproduces existing inequalities, as training programmes tend to benefit the better‐educated and younger segments of the population while leaving behind older or low‐skilled workers (Centeno & Novo, 2014).

In this context, understanding how training programmes targeting low‐skilled unemployed individuals operate at the local level—both in terms of their design and implementation—is crucial to assessing whether the EU’s social investment agenda can deliver on its promises of inclusive and sustainable growth.

6. Historical Institutionalism and the Analysis of National Policy Specificities

Historical institutionalism, like other strands of the “new institutionalism” (Hall & Taylor, 1996), is grounded in the idea that institutions matter: they shape actors’ preferences, constrain their choices, and structure policy outcomes over time. Unlike rational choice or sociological institutionalism, however, historical institutionalism emphasizes temporality, path dependency, and the cumulative effects of past decisions on current institutional configurations.

In this framework, institutions are not static; they evolve through mechanisms such as layering (adding new elements without removing old ones), conversion (reinterpreting existing rules), drift (changes in the environment that alter institutional effects), and displacement (replacement of old institutions by new ones) (Mahoney & Thelen, 2010). These gradual modes of change often explain why policy reforms—especially in highly institutionalized domains like labour market regulation or social protection—rarely produce radical transformations.

Applied to the analysis of EU social policies, historical institutionalism helps explain why the diffusion of activation and social investment principles across member states has led to convergence in discourse but divergence in practice. While supranational frameworks promote similar goals (employability, upskilling, inclusion), their translation into national contexts depends on pre‐existing institutional legacies, administrative capacities, and political coalitions.

In Portugal, the institutional legacy of a corporatist and bureaucratic welfare regime, combined with fiscal constraints and fragmented governance, has limited the capacity of public employment services to implement activation measures effectively. The Portuguese Employment and Vocational Training Institute (IEFP) operates within a complex web of rules and accountability mechanisms that prioritize procedural compliance over individualized support and innovation. As a result, while the rhetoric of activation and lifelong learning has been fully embraced, the practical delivery of training and employment services remains constrained by rigid administrative procedures, limited resources, and the absence of sustained coordination between local, national, and EU levels.

The following figure summarizes the conceptual framework guiding this analysis:

Figure 1. Conceptual framework: Historical institutionalist analysis of EU social policy implementation in Portugal

(Note: Diagram omitted in text format — includes relationships among EU policy frameworks, national institutions, and local implementation dynamics.)

7. Institutional Barriers and Labour Market Challenges in Portugal

The following section analyses a range of factors that help explain the shortcomings of training programmes and the institutional barriers hindering the effective inclusion of vulnerable groups in the labour market and broader society.

First, the design of many training programmes remains largely supply‐driven, focusing on fulfilling administrative targets—such as the number of trainees enrolled or the total hours of training delivered—rather than responding to actual labour market needs. Interviews with caseworkers revealed that course offerings are often determined by the availability of accredited training providers and predefined funding streams rather than by systematic labour market assessments or employer consultations.

Second, the bureaucratic rigidity of programme management frequently clashes with the complex realities of participants’ lives. For example, full‐time attendance requirements and the lack of flexibility in scheduling make it difficult for individuals with caregiving responsibilities or informal jobs to participate consistently. Moreover, delays in stipend payments and transportation allowances often discourage participation, particularly among those with limited financial means.

Third, limited coordination between the IEFP and other public or private stakeholders constrains the effectiveness of training programmes. Local employers are seldom involved in course design or evaluation, which reduces the likelihood that trainees acquire skills aligned with current or emerging job opportunities. Similarly, insufficient collaboration between employment services and social assistance agencies hampers the provision of integrated support for individuals facing multiple barriers to employment (such as long‐term unemployment, health issues, or low literacy).

Fourth, the evaluation of programme outcomes remains largely quantitative and short‐term. Success is often measured by immediate job placement rates, without systematic follow‐up to assess the sustainability or quality of employment obtained. This narrow focus neglects the broader social and personal benefits of participation, such as improved self‐confidence, social inclusion, or progression to further education and training.

Finally, the COVID‐19 pandemic further exposed the fragility of Portugal’s training and activation system. While the pandemic accelerated the digitalization of many services, it also highlighted the digital divide affecting older and low‐skilled individuals, who often lacked access to reliable internet connections or basic digital literacy. This exacerbated existing inequalities and reinforced the need for more inclusive and adaptive training approaches.

8. Discussion and Broader Context

8.1 Reconciling Social and Ecological Goals

As the world faces unprecedented environmental challenges that threaten both human society and the physical environment, the social implications of global ecological risks—identified by Beck (1992) several years ago—have become even more evident. The European Green Deal and the European Pillar of Social Rights represent an effort to integrate environmental sustainability with social justice, emphasizing that the ecological transition must be fair and inclusive.

However, achieving a “just transition” requires more than policy declarations. It demands a reconfiguration of production and employment structures, accompanied by comprehensive strategies for skills development and social protection. Training programmes targeting low‐skilled unemployed individuals can play a crucial role in this process, but only if they are effectively aligned with emerging sectors and designed to empower participants rather than merely recycle them through bureaucratic processes.

8.2 Portuguese Policy Limitations

In the Portuguese context, this alignment remains weak. While national and EU frameworks emphasize digital and green skills, the translation of these priorities into concrete training content and employment opportunities is limited. Most courses continue to focus on traditional occupations with low technological and ecological relevance, reflecting the inertia of existing institutional and economic structures.

Moreover, the persistent gap between national policy rhetoric and local implementation underscores the importance of institutional capacity and autonomy. Caseworkers and local managers often operate within tight constraints, balancing the need to meet administrative targets with the desire to provide meaningful support to participants. This tension illustrates the broader challenge of transforming bureaucratic systems into learning organizations capable of innovation and adaptation.

In sum, while EU‐level initiatives such as the EPSR and EGD provide an important normative and financial framework for advancing social and ecological goals, their effectiveness ultimately depends on the capacity of national and local institutions to internalize and operationalize these objectives. The Portuguese case reveals both the potential and the limitations of such efforts, highlighting the need for greater institutional coordination, flexibility, and learning at all levels of governance.

9. Conclusion

Three key themes emerging from this research warrant further examination.

First, the analysis underscores the enduring influence of institutional legacies in shaping national responses to supranational policy agendas. Despite the proliferation of EU‐level initiatives promoting activation, skills investment, and just transition, their implementation in Portugal remains constrained by entrenched bureaucratic routines, limited resources, and weak coordination mechanisms.

Second, the findings highlight the ambivalent role of front‐line actors—particularly caseworkers—who operate at the intersection of policy design and delivery. Their discretionary practices can either mitigate or exacerbate institutional rigidities, depending on their professional autonomy, workload, and organizational support. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for designing policies that are both effective and responsive to local realities.

Third, the research calls attention to the need for a more integrated approach to social and ecological policy. The transition to a green and digital economy must be accompanied by robust social investment in human capital, targeted support for vulnerable groups, and institutional reforms that enhance learning, coordination, and adaptability.

More Posts

- The Role of Teachers in Developing Students Emotional Intelligence [2025]

- Skills do you need most to give a good speech at school

Hi, I’m Anshul Patel, author and co-founder of TigerJek.com. I am a long-time Roblox and mobile gaming enthusiast with 6+ years of gameplay experience. I test every method, build, and strategy personally before writing guides for TigerJek. My goal is to simplify complex games and help players progress faster.